A new term — an accompanying phenomenon — emerged in 2023: “clout bombing.” This arose in relation, most pointedly, to Marc Jacobs’ Heaven campaign, which featured, as its central advertising push, an absolutely massive couch populated by a variety of not only celebrities and models, but also culturally-relevant micro-influencers and writers, editors, and artists.

A cynic would say that brands are trying to cover themselves in the patina of borrowed intellectualism and cultural prestige to sell neo-goth, threadbare sweaters and shirts.

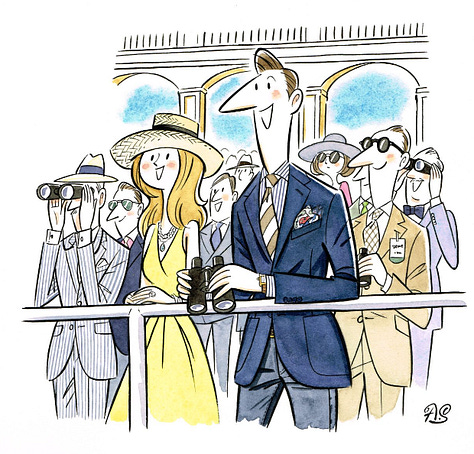

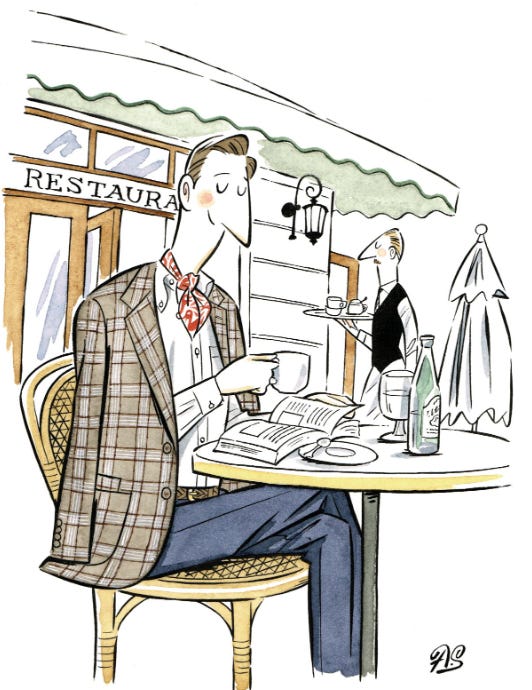

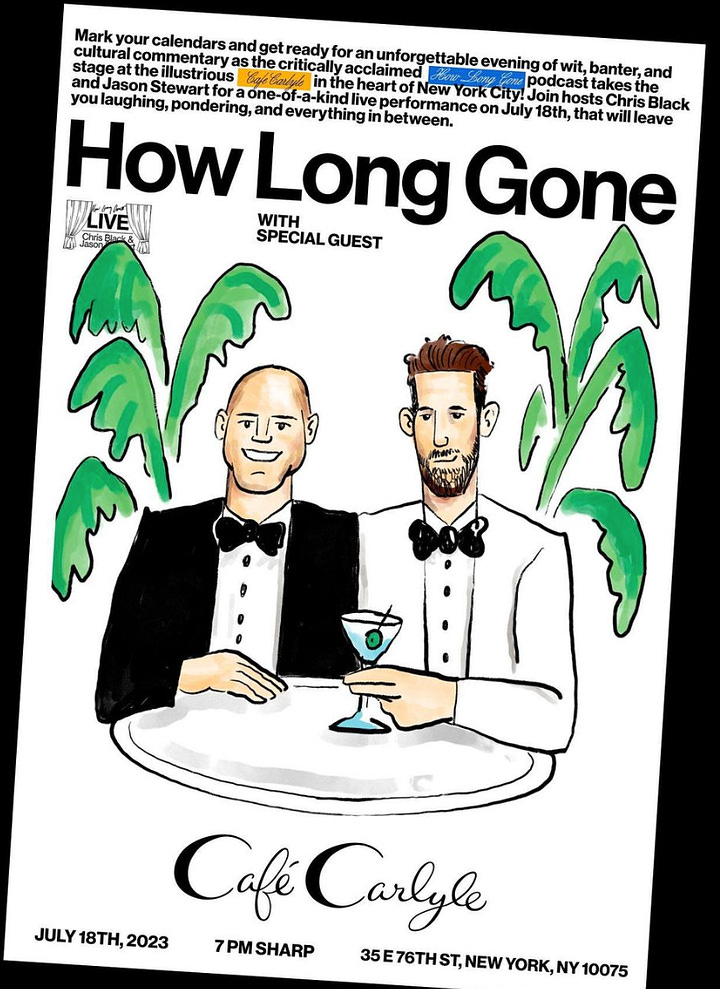

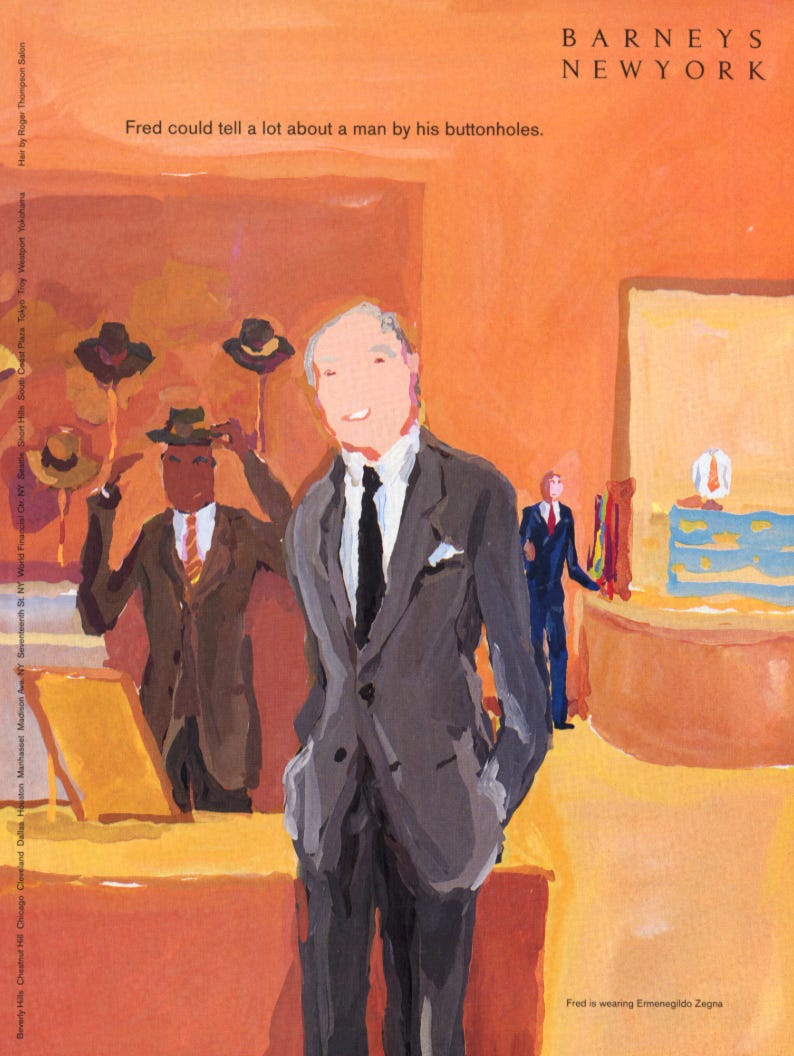

A related trend has emerged more recently: that of the quirked-up, pseudo-New Yorker-style cartoons popping everywhere from podcasts to purveyors of ~$400 tiger scarves. Who knew the former province of desert island shrinks could be adapted to dressing in double-breasted suits and standing around Canal Street?

The illustrations imbue the act of buying Aimé Leon Dore-branded New Balances or the taping of a live podcast with highbrow aura of attending a heady Paris Review gala or launching of a literary journal.

Perhaps the most artful negotiator of this high-brow and high-thread-count balance in the present day is Graydon Carter: éminence grise of golden-era Vanity Fair and now co-creator of the digital glossy Air Mail. Air Mail the mag has also yielded Air Supply, the aspirational shopping vertical, and Air Mail Newsstand, an even more eye-wateringly aspirational brick-and-mortar in the West Village.

In spirit, Air Mail’s cartoon style is indebted to the New Yorker’s. (Indeed, ex-New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff is now cartoon editor at Air Mail.) Perhaps what Air Mail capitalizes on so perfectly is a nostalgic vision of urbanity backed by equal parts mental stimulation and aesthetic overload—a wish that one could be firing off journalistic missives from Monaco or Marseilles with a perfectly retro Montblanc pen and paging through rare French Vogues.

A forebear to this “luxury goods to magazine pipeline” is Glenn O’Brien, the first editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine, and a champion of the “business art”—that is, business as a form of art—his mentor Andy Warhol professed.

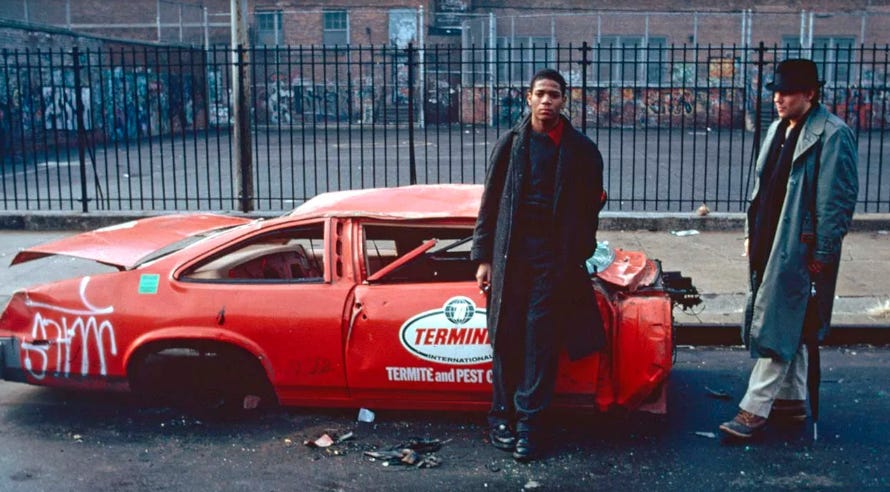

Aside from a pivotal role at Interview, O’Brien came to prominence as the holder of the following unimpeachable credits: editor of Madonna’s Sex book, writer of the rare Jean Michel Basquiat vehicle Downtown 81, co-founder of BOMB magazine, and host of the influential public-access show TV Party (guests including Basquiat, Debbie Harry, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Byrne, et al).

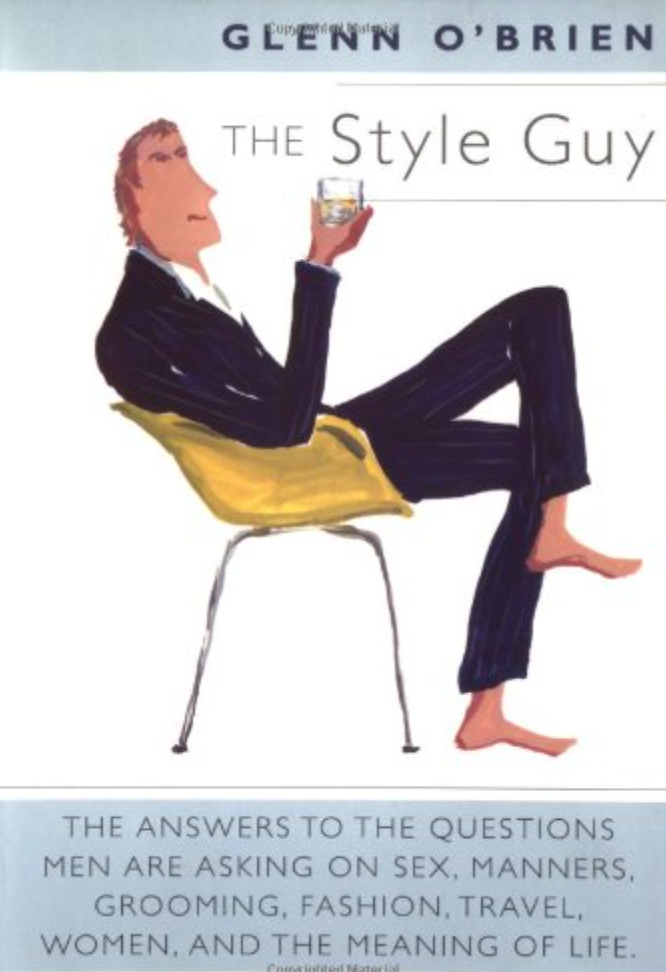

After this initial multidisciplinary foment, O’Brien proved equally adept at cultural criticism — writing a long-running column on advertising, “Like Art,” for Artforum, and espousing Wildean life principles as GQ’s “Style Guy”—and high-brow, luxury ad campaigns. His specialization, as an advertisement consigliere, was in approaching the possibilities of the commercial form from a downtown, avant-garde perspective. Advertising that was not quite art, but in the phrasing of his Artforum column, like art.

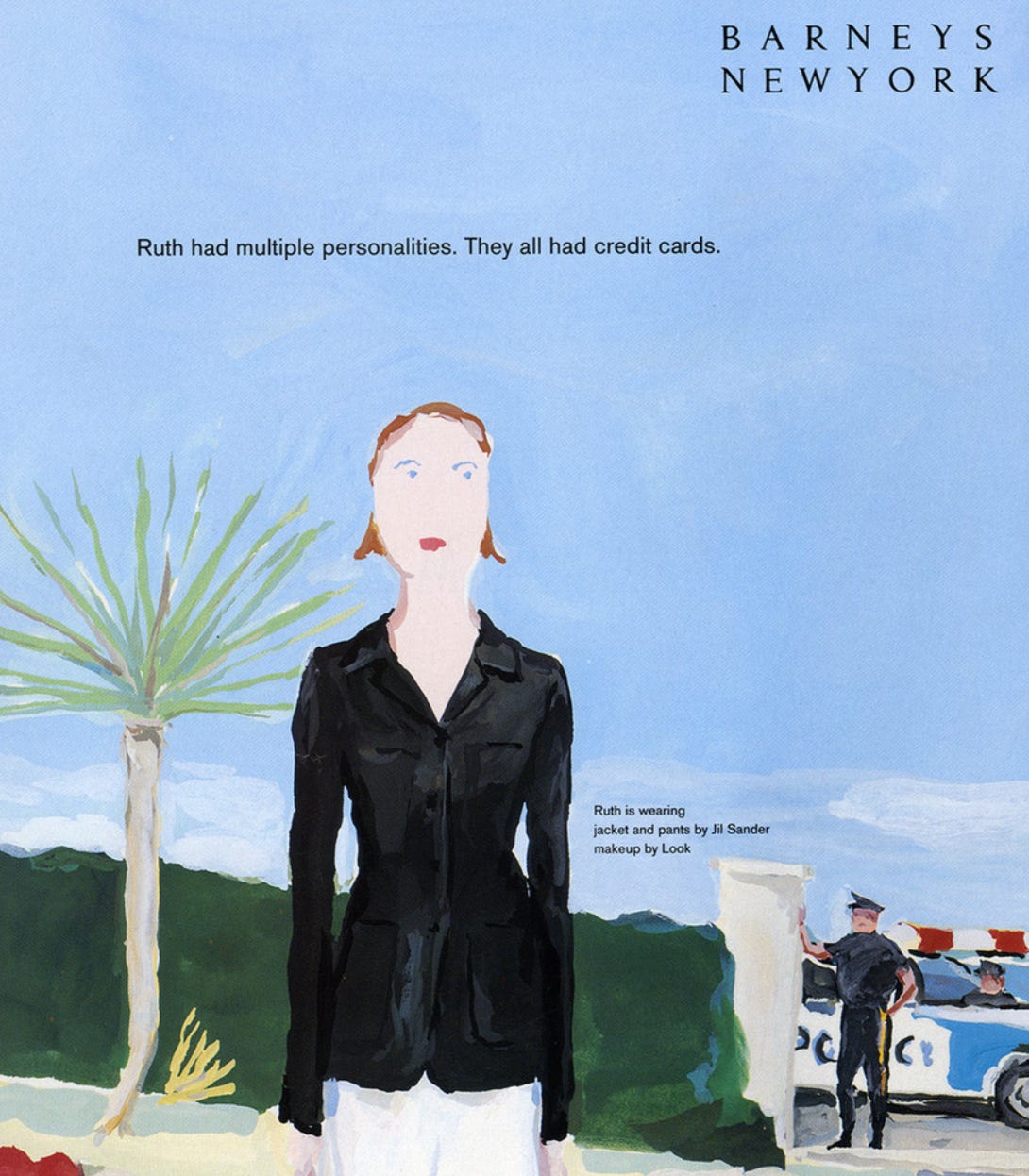

In his later, post-Interview role as creative director of Barneys (RIP), successful copywriter for hire, and owner of his own ad shop, his commercial work cultivated a cool Downtown detachment. He tested, and capitalized on, the ambiguity between financial and theoretical expressions raised prominently during the rise of Pop Art.

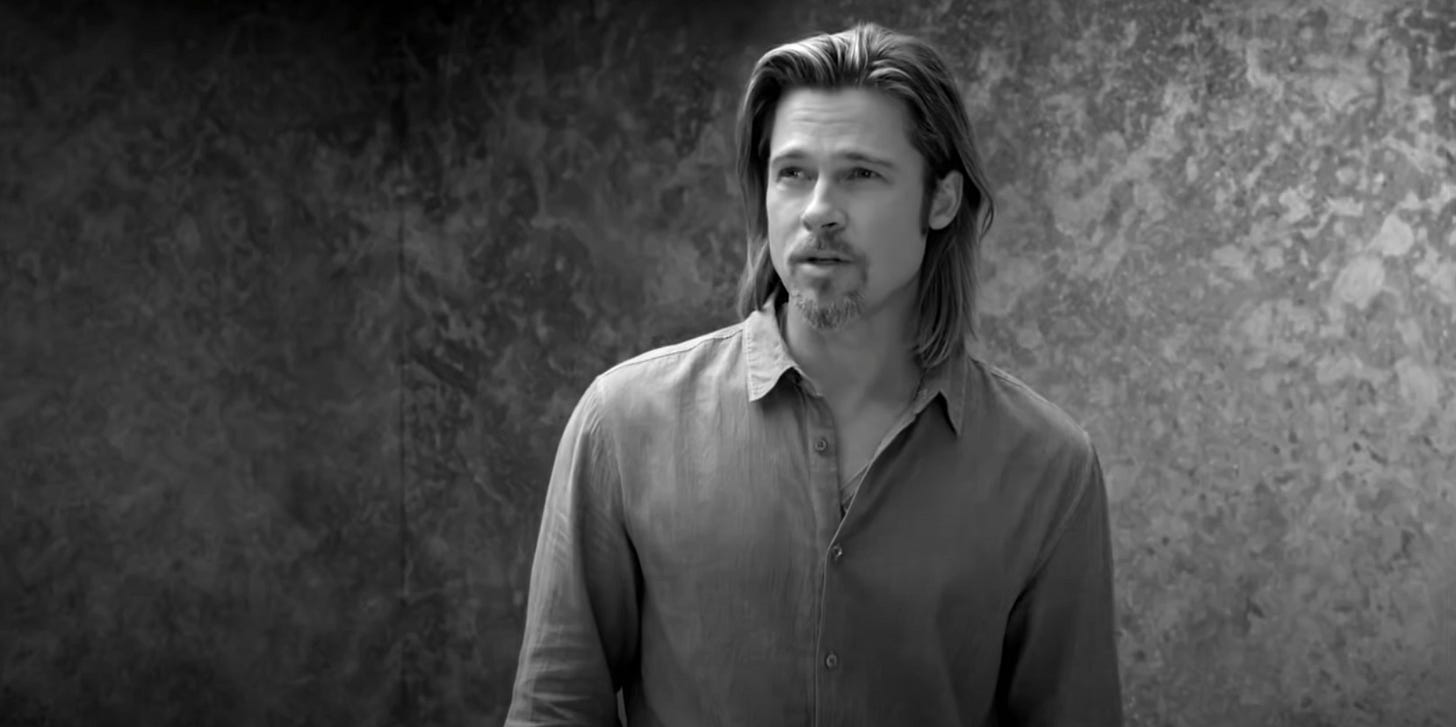

Indeed, O'Brien saw what he was doing — in campaigns like this Chanel No. 5 ad, the infamous Markey Mark underwear ads, or a provocative cK One ad series, investigated by the Clinton Justice Department — as “art—with a logo.”

O’Brien points to artists like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst as having logos “like Audi or Mercedes.” Their work, too, creates their own iconic, branded shorthands as much as it pulls from the surrounding world of products, prescriptions, and cartoons.

The fuzziness of art enterprise and commercial enterprise was replicated, to O’Brien, in the Citizens United Supreme Court decision. “Corporations, which began as legal persons, are now mutating into actual persons, with opinions and personalities. I found a de facto manifesto for the emerging corporate personality in an ad.”

To O’Brien, the short-hand of the high-brow, in the context of commercial enterprise is for all the better—a Medici-like program to fund art practice in the furtherance of flatscreen or flat brim sales. However, there always seemed to O’Brien’s practice the bracingness of the avant-garde. Some way that the ad or commercial art work fundamentally jostled or jolted the consumer—the strangeness and alienation part of the outré cool fostered on the products behalf. Without it, per O’Brien, you’re just selling toothpaste.

He was overrated.